A Dutch Foundation is a Dutch legal entity with limited liability but has no members or share capital. If you plan to start a Dutch foundation, there are a lot of considerations to factor in.

But first, what is a Dutch foundation? A Dutch Foundation (Stichting) is a unique legal entity, which can be viewed as the ‘civil law’-equivalent of the Anglosakson ‘trust’. Whereas the ‘trust’ is not a legal entity, but rather a ‘trust deed’, the Foundation is a (self-owning) corporate entity, without any share capital or shareholders. This means the Foundation can own assets, a bank account, and even decide to perform profitable or non-profitable activities (to which different tax treatments apply).

Some companies start a Dutch Foundation because it can be effective as an asset protection tool. Family companies like IKEA have set up their own Dutch Foundation to protect their group structure. More recently companies, like ABN Amro and ING, have been listed on the Dutch stock exchange via a Foundation structure. As a result, there is a limitation on the (voting) rights of investors. This protects the company by empowering the Board of Directors optimally.

A Dutch Foundation will not be subject to corporate income tax or VAT when it solely holds a foundation. Because it is considered a ‘legal person’, a Dutch foundation can be the top entity in a group structure and be recognised as the ultimate beneficial owner or UBO.

What is a STAK?

If you intend to start a Dutch foundation, it is important to know STAK. STAK, short for Stichting Administratie Kantoor, is an application for the Dutch foundation. Once you’ve set up your Dutch foundation, and it has started acting as the shareholder of Dutch BV (or other Dutch entity), we start calling it a STAK. The STAK will issue profit certificates to the investors/shareholders involved (basically, in exchange for the shares of the BV).

NGO/charitable organisations

The Dutch Foundation is a so-called ‘orphan entity’ without any shareholders, and can avoid any corporate taxes. Charitable organisations and NGOs widely adopt this vehicle. If you have plans to start a Dutch foundation, establish a Dutch charity or start an NGO in the Netherlands, our team can assist you every step of the way.

Guide #1 Corporation income tax for the Dutch Foundation

Foundations are only liable for corporation tax if and insofar as they operate a business. It follows that (1) an enterprise must be and (2) only tax must be paid on the benefits arising from the conduct of the business.

- A foundation drives an enterprise when a sustainable organisation of capital and labour takes part in the economic trajectory (not in a closed circle) with the intention of making a profit. The behaviour of a body must show that systematic achievement of advantages over costs is sought. A chance surplus will not result in tax liability for corporation tax, as long as it does not become a systematic surplus. If the foundation competes with companies, then the foundation is also expected to drive a business. Then the effectiveness of the foundation must be at the expense of the revenues of other companies. Subsidies are included in the tax base for corporation tax purposes. As a result, it may be that systematic surpluses arise. Therefore, the foundation becomes liable to pay taxes. However, the State Secretary has decided that no profit pursuit is deemed to exist if the surpluses: (a) have to be used in accordance with the subsidy objective or (b) must be paid back to the subsidy provider.

- If the tax authorities determine that the foundation is operating a company, then only tax must be paid on the benefits arising from the company. Payments from generosity (donations) by persons who have no interest in the company’s business operations do not constitute benefits derived from the foundation’s business operations. On the other hand, sponsoring that, for example, is advertised, is an advantage that follows from the conduct of business. Sponsoring is therefore included in the tax base.

Some special arrangements:

- Taxable foundations that do not make profits of more than € 15,000 annually are exempt from tax.

- ANBIs that mainly earn their profit with the help of volunteers (no wages or lower wages than usual), may, under certain conditions, deduct the costs that would also be deductible if the reward were to be made on the basis of the minimum wage (in some cases: the usual wage), less the actual costs.

Bolder Launch can draft a specific tax memo for your situation. Our tax lawyer can prepare a quote based on your questions and requirements. This way, you can determine the tax consequences and ask for advice on the tax structure.

Guide #2 ANBI (or SBBI) status

Benefit institutions can enjoy certain tax benefits. The ANBI is the most commonly known charity status, but the SBBI status is much easier to obtain. Donations to ANBIs are deductible for income tax or corporation tax. Under certain conditions, ANBIs may be exempted from inheritance and donation tax, transfer tax and a reduction of energy tax.

The activities of the institution must actually serve 90% or more of the public interest. It should also function according to the articles of association. In addition, a number of other conditions apply.

- Do not have a profit motive. However, it is not enough that the regulations show that the institution does not have a profit motive. The actual behaviour must also be in line with this. Incidentally, it is not the case that an ANBI that, incidentally, makes use of operating surpluses and uses them for the benefit of the public benefit, immediately has a profit objective with its actual activity.

- Use exclusively or almost exclusively the public interest.

- No right of disposal over the assets of the institution for natural or legal persons.

- Maintain an equity ceiling.

- A remuneration restriction for the policymakers.

- An up-to-date policy plan.

- A reasonable ratio of cost to spending.

- Provide for correct spending of a positive liquidation balance.

- Meet requirements regarding the organisation of the administration.

- Make certain information public via the internet.

From 2010 onwards, an integrity test is being applied.

Marking as an ANBI takes place at the request of the institution. The inspector decides on the request by a decision that can be objected to, possibly under conditions to be set by him.

Although obtaining the ANBI status will improve the reputation of your charitable organisation, the advantages will be very limited as long as your charity is operational on a global scale. The tax credits available to donors will typically not apply to non-Dutch donors (or would apply even if such status would not be available). When your charity works with corporate donors, the advantages are also limited.

Should you go for the ANBI status? We advise you do your research first if the ANBI status will allow you to enjoy tax advantages you need for your charity. It is important you do this before you decide to adjust your corporate structure, according to the ANBI requirements. We suggest contacting our Launch Team for assistance.

Guide #3 Formation process of the Dutch Foundation

It’s straightforward to start a Dutch foundation. It is very similar to setting up a Dutch BV. Check out our Dutch Foundation formation services here.

A Dutch foundation requires the involvement of only one individual or corporate entity. This individual will act as a board member and/or treasurer/secretary.

If you have a more complicated structure in mind (for example, you want a supervisory board), there might be additional fees to ensure the Formation Deed is adjusted based on your requirements

It’s common practice to visit the Netherlands to establish the Foundation. You are required to visit the Netherlands if you wish to open a corporate Dutch bank account.

There is no legal requirement to open a Dutch bank account to deposit the share capital of the company or run the business. If you do not wish to open a Dutch bank account, you might be eligible for a remote formation, which means you will be able to register your company from your home country. Please contact us if you have any questions about what type of formation would suit your situation best.

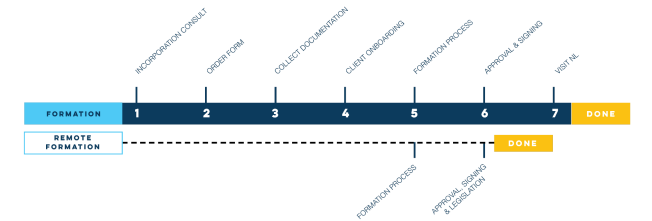

When starting a business in the Netherlands, keep the timeline below in mind. The top bar reflects the timeline for our most sold service, which includes support in obtaining a bank account and demands a visit to the Netherlands. The bar below (with the dotted line) reflects the timeline for a remote formation, which could interest you if you don’t need a Dutch bank account. This will save you the trip to the Netherlands, but it is more costly.

How much does it cost to start a Dutch foundation? Check our service page here, where you can see our offers, the exact procedures and the cost to set up a Dutch charity or start an NGO in the Netherlands.

Matters to consider before the formation

- Profit receipts can be issued to investors or shareholders, which allows them to take profits, but without getting any voting rights. In effect, legal ownership is separated from economic ownership. Multinationals prefer this setup, in order to prevent hostile takeovers, and put more power at the level of the board of directors. For tax purposes, profit certificate holders are typically treated equally as shareholders. It is not required to issue profit certificates at formation. You can do this at a later stage. Please note that only profit certificates can be issued if there is also a Dutch B.V. as a subsidiary of the foundation. In effect, the foundation will be the legal owner, while it ‘transfers’ the economic ownership by issuing profit certificates. We call this setup the ‘STAK’ (Stichting Administratiekantoor).

- It does not require tax registration in the Netherlands if it is only involved in passive investments owning real estate, stocks, shares, etc.

- The foundation requires only one director, who can be a non-resident corporate entity.

- It can voluntarily register for taxes when it becomes ‘operational’. Even if it becomes operational, it’s not required to register for taxes (or pay taxes) as long as the profits do not exceed €15.000 EUR per year.

Guide #4 Legal considerations when setting up a Dutch Foundation

When you intend to start a Dutch foundation, you have the option of a robust and flexible tool to manage private wealth. This is because beneficiaries do not have any direct interest in the Dutch foundation, but the family may retain control over the autonomous board by various indirect means. If the assets originate from non-residents exclusively, the use of a Dutch foundation may also be very tax-efficient. Despite the existence of high gift and income tax rates, the use of a Dutch non-charitable, private foundation provides a flexible dynastic structure for combining charitable and private purposes in an unregulated and effectively tax-free environment.

A Dutch private foundation is a very attractive device for dynastic structuring of international wealth, especially for non-resident families. Specifically, the Dutch foundation can be an alternative to a charitable organisation without the detailed administrative and tax oversight rules. Here are the advantages you get when you start a Dutch foundation:

- Solid asset protection

- With effective (indirect) control by the family

- Without accountability towards beneficiaries

- Very flexible

- Effective exemption from Dutch tax when used by non-resident families

The essential feature of a Dutch foundation is that it is a legally autonomous entity with rights and obligations but without any owner or persons with an interest therein. It is without members and its purpose, with the aid of funds intended for such purpose, is to realise the objects set out in its articles of association (Book 2 Article 285 (1) of the Dutch Civil Code).

Accordingly, the foundation may be called a ‘purpose fund’. More specifically, Dutch civil law provides for the following features of a private foundation:

- A Dutch private foundation is fully independent of the founder. The founder has no special or reserved founder’s rights and accordingly, there are no ‘controlling rights’ whatsoever that can be assigned to third parties

- The group of beneficiaries that would normally be mentioned in the purpose and activities of the foundation, as set out in the articles of association, does not have any interest in the assets of a private foundation nor does there exist any right of information on the foundation assets or reporting towards this group. However, it is possible to assign specific rights or entitlements to designated beneficiaries in the governing documents of a private foundation

- The board of the foundation has no fiduciary duties, but it is the representative of the full ownership of the assets similar to the board of a company. If a board member is acting in breach of his duties, he is liable to the foundation (the foundation is required to act in the sole interest of its stated purpose, which in the case of a private foundation, is to serve the interest of private purposes such as the pursuit of interests of family members). In case of mismanagement by the board of the foundation vis-à-vis the foundation, any interested person (including a beneficiary) is able to apply to the Court to dismiss the board member(s). Dutch law does however not know an enforcer that is able to enforce statutory objectives.

- In practice, it is perfectly possible for a family to retain control through a Family Council that acts as a Supervisory Board to the private foundation. The supervisory board will have strong controlling powers, including the right to appoint and dismiss board members. It will also have the right to full information on the assets and activities as well as reporting of the private foundation. Family control may eventually be increased by a family representation on the board of directors.

- Apart from the articles of association, a foundation may have one or more regulations in place. These will regulate the activities of the foundation and its respective organs in greater detail; the contents of these regulations remain fully confidential.

- The founder is not as important to a Dutch private foundation as the person who transfers assets to the foundation (the transferor). The transferor enters into a separate (transfer or gift) agreement with the private foundation, which may contain various reserved powers, stipulations and conditions as to the transfer to the foundation. Typically, the agreement provides for exit scenarios. Nonetheless, this does not deprive the board members of the foundation of their autonomy over the general operations of the private foundation. Needless to say, the stipulations in the transfer agreement should not exceed a certain level that would deprive the board of its autonomy.

- Rather than transferring the full ownership to the private foundation, it is possible for the family to retain voting power over the transferred assets. That is through a combination of a private foundation and a fiduciary foundation (Stichting Administratiekantoor) that only has the voting power over the assets; the latter being managed by the family members.

Structured with caution, a Dutch private foundation offers a very solid asset protection structure, which is apt for tailor-made family governance design. Family members who are ‘beneficiaries’, as defined in the statutory purpose of the private foundation, do not have any interest in the family foundation or its controlling body unless the governing documents would provide so specifically.

The board of directors may be controlled by a supervisory family council and staffed by family members if desirable. It can also be bound by the stipulations in a transfer agreement, whilst at the same time, the board of directors has ultimate autonomy over the operations of the foundation.

A Dutch private foundation may hold shares in active business corporations, passive investment funds, art collections etc. Therefore, it may be suitable for the dynastic structuring of important assets of families. There is one legal issue relating to private foundations used for dynastic structuring that has raised some debate in the Dutch legal doctrine since 2010.

One of the few compulsory provisions in the Dutch Civil Code prohibits the purpose of the foundation to include making payments to its founders, to persons who constitute its organs or to others. This is unless the payments have an altruistic or social character. This prohibitive condition is aimed at using the foundation as an alternative to the legal form of a commercial corporation. It is therefore arguable that this prohibition does not apply to family foundations that do not carry on an enterprise. In addition, the objective to pay distributions to family members (including founders or persons who are staffing the organs of a foundation) for appropriate purposes (study, maintenance, health treatments) qualifies as ‘social’. It can therefore be said that the prohibition aims to avoid the objective of a foundation creating a ‘selfish’ foundation.

Moreover, where the transferor wishes that the board of the foundation makes distributions to designated family members or for designated purposes, the transferor can stipulate these wishes in the contractual ‘gift’ agreement with the foundation. To summarise, in practice, this restriction is overcome by a combination of tailor-made drafting of the constitutional documents and the gift agreement between the transferor and the foundation. It is beyond doubt, that the private foundation is very suitable to combine dynastic family purposes and ‘altruistic’ purposes.

Due to the special tax regime in the Netherlands (as referred to hereunder), it is irrelevant whether these altruistic purposes would qualify as charitable or not. The introduction of the new Segregated Private Capital regime (Afgescheiden Privaat Vermogen (APV), introduced in art 2.14a Income Tax Act 2001.) was inspired by the wish to disregard foreign purpose funds like trusts, establishments (Anstalten), private foundations being used to ‘shelter’ funds and to impose taxes upon the original owners or their beneficiaries with a view to the structured funds therein. In order, however, for such legislation to remain ‘EU proof’, an abstract definition— independent of the place of registration and legal form—was introduced: the APV.

Consequently, private foundations registered in the Netherlands also qualify as an APV. This APV doctrine has introduced the fiction that all income and assets of all ‘Segregated Private Capital’ will be attributed for tax reasons to the transferor alone or, after his or her passing away, to the respective heirs. Furthermore and as a consequence of the above, the tax laws treat all transfers to and from legal vehicles that qualify as Segregated Private Property as non-existent solely for Dutch tax purposes.

A private foundation is not qualifying as an APV to the extent that it has issued or designated specified entitlements to third parties against the transfer of property into the foundation. The APV regime therefore only applies to the extent that there is no interested party in relation to the assets and the income of the foundation that may be subject to tax on it. Also, charitable foundations and foundations that pursue social interests are excluded from the scope of the APV regime.

After the death of the contributor, these are fictitiously attributed to his or her heirs in proportion to the share of the total estate that each beneficiary is entitled to under applicable inheritance laws. There is only a liability to Dutch income tax if the contributor or his heirs is or are tax subject in the Netherlands in respect of the attributed funds or the income derived thereunder. Unless the APV acquires Dutch situs assets that submit the transferor and his family to non-resident taxation in the Netherlands, there will be no Dutch income tax involved presumed that the transferor or his/her beneficiaries/ heirs would not take up residency in the Netherlands in the future.

Lastly, distributions by Dutch private foundations that qualify as APV will not be subjected to Dutch gift tax in these circumstances, since the beneficiaries are deemed to have acquired their benefit directly from the transferor (who is not subject to Dutch gift tax) or, after his/her decease, the respective heirs. For the purposes of gift and inheritance tax liability, the separation of funds within an APV is disregarded and accordingly, payments made from an APV foundation are deemed to have been acquired from the person or persons to whom the funds of the APV are attributed for the purposes of levying income tax. In the Act and in the parliamentary records the term ‘separation of funds’ has been given a very broad definition. It includes disposals and the separation within companies held by individuals is also deemed to be founded on the private interest served by the APV, and, accordingly, the separation can be followed through to the underlying shareholders of a ‘separated’ company.

Although the Dutch tax legislation does not specifically refer to the transparency of the APV, this in fact may be said to be the purpose and aim of this legislation. The Dutch private foundation has recently developed into a robust but very flexible tool to manage private wealth.

Beneficiaries do not have any interest in the Dutch foundation, whilst the family may retain control over the autonomous board by various indirect means. If the assets are acknowledged to be originating from non-residents exclusively, the use of a Dutch foundation may be very tax efficient. Despite the existence of high tax gift and income tax rates, the use of a Dutch non-charitable, private foundation provides a flexible dynastic structure for combining charitable and private purposes in an unregulated and effective tax-free atmosphere for non-Dutch families that refrain from taking up tax residence in the Netherlands.

General information on how to start a Dutch Foundation

Basis of Legal System | Civil Law |

| Type of Company | Foundation (‘Stichting’); self-owning entity |

| Exchange Controls | None |

| Redomiciliation Permitted | Yes |

| Shelf Companies Available | No, ‘same day’ formation is possible |

| Timescale for new entities | On average 3-5 days |

| Formation Fee | €1.800 (incl. notary charges, etc.) |

Corporate and Taxes

| Minimum Share Capital | Not applicable. No shares are issued. |

| Minimum Shareholders | Not applicable, however, ‘depository receipts’ can be issued to ‘economic owners’ |

| Minimum Directors | 1, can be corporate and non-resident |

| Taxes | The Foundation is not liable for any taxes, as long as the commercial profits are less than €15.000 |

| Allowed Activities | All activities are allowed, even commercial activities. However, only the passive investment activities are considered tax free, which includes holding assets such as shares/real estate, etc |

| VAT Number | Applicable in case of commercial activities only |

Public Filings

| Directors | Yes |

| Shareholders | Not relevant. ‘Depository Receipt’ – holders will also not be public |

| Beneficial Owners | No |

| Issued/Paid up Share Capital | Not relevant |

| Memorandum and Articles of Association | Yes, but By-Laws can remain private |

Annual Filing Requirements

| Audited Financial Statements | No, unless commercial activities |

| Annual Filing to Tax Authorities | No, unless commercial activities |

| Issued Share Capital | No, not relevant |

This guide is part of Company Formation in our Launch Guide.